101-year-old Josef Schuetz, the oldest person to go on trial for Holocaust crimes, was found guilty of being accessory to murder at Sachsenhausen camp and was handed a five-year jail sentence.

A German court on Tuesday, June 28, found the 101-year-old Josef Schuetz guilty of being an accessory to murder while working as a Nazi concentration camp guard at the Sachsenhausen camp in Oranienburg, north of Berlin, between 1942 and 1945. Presiding judge Udo Lechtermann sentenced Schuetz to five years in prison.

With his 101 years, Josef Schuetz is the oldest person to go on trial for complicity in war crimes during the Holocaust. The pensioner, who now lives in Brandenburg state, had pleaded innocent, saying he did “absolutely nothing” and was not aware of the gruesome crimes being carried out at the camp, reports The Times Of Israel. However, during the trial, Schuetz made several inconsistent statements about his past, complaining that his head was getting “mixed up.” On Monday, he said “I don’t know why I am here.”

Prosecutors claim he “knowingly and willingly” participated in the murders of 3,518 prisoners at the camp and called for him to be punished with five-year sentence.

More than 200,000 people, including Jews, Roma, regime opponents and gay people, were detained at the Sachsenhausen camp between 1936 and 1945, and tens of thousands of inmates died from forced labour, murder, medical experiments, hunger or disease before the camp was liberated.

Prosecutors said Schuetz had aided and abetted the “execution by firing squad of Soviet prisoners of war in 1942” and the murder of prisoners “using the poisonous gas Zyklon B.” He was 21 years old at the time.

Schuetz’s trial began in 2021 but has been delayed several times because of his health. Despite his conviction, he is highly unlikely to be put behind bars, given his age.

More than seven decades after World War II, German prosecutors are racing to bring the last surviving Nazi perpetrators to justice. While some have questioned the wisdom of chasing convictions related to Nazi crimes so long after the events, Guillaume Mouralis, a research professor at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), said such trials send an important signal.

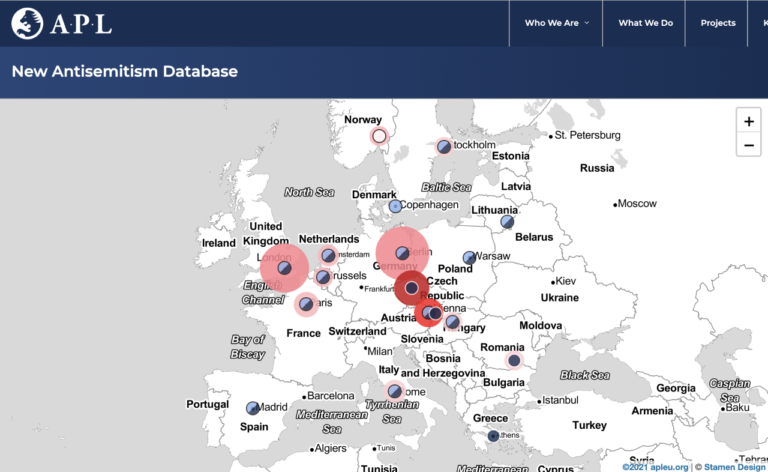

“It is a question of reaffirming the political and moral responsibility of individuals in an authoritarian context (and in a criminal regime) at a time when the neo-fascist far right is strengthening everywhere in Europe,” he told AFP.